Book reviews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Fan of Barbarism

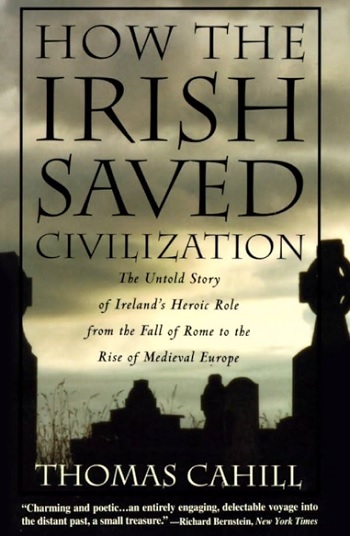

Review of How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe; Thomas Cahill, (Doubleday, 1995), 246 pp.

This is the ostensible premise of Thomas Cahill’s book How the Irish Saved Civilization. At face value this has historic merit. Following the collapse of Rome, many Irish monks and preachers spread throughout the freshly barbarized Continent and brought with them lost arts of civilization.

The way Cahill presents this information, however, lends a rather different flavor to the text. From presenting a tale of historical value the story veers into what may be the true intention of his book: a nostalgic admiration for the raw savagery of the barbarian.

The noble savage

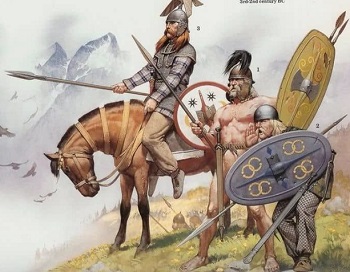

Cahill spends an inordinate amount of his book studying the rude and uncivilized barbarians of this period with outright admiration. Though coarse, dirty, unkempt and destructive, the barbarians are presented as living a purer carefree life, an existence unencumbered by the rigid discipline, formulas and even logic of Catholic Roman world. It becomes apparent that Cahill has fallen for the myth of the Noble Savage, only this time instead of Indians it is the barbarians of Northern Europe that are held up as a model of authentic living.

Cahill admires the coarse & vulgar barbarians of the age

It is the same tired arguments we see today: Civilization is constricting the human spirit, we would all be better off if we “unschooled” our children, we should return to live in a state of nature. But Cahill does not stop there. From looking on the barbarians of Europe with the admiring eye, Cahill fills his book with denigrations of the true Faith.

Disdain for religious purity

While Cahill extols barbarians, Roman Christendom is deplored. The author seems to take an almost mischievous pleasure in asserting that many Catholic feasts and traditions are merely a pagan leftover from a barbarian past.

Pre-Christ Judaism is not spared the author’s disdain. The Temple of Solomon is scorned. Jewish thought from the pre-Messiah times is deliberately cast in a negative light while Scripture, he insinuates, is more allegory than reality.

The wise St. Augustine is cast as one of histories greatest villains

St. Benedict too is held up an archetype of a “dead order” which forces its victims to fit into a Procrustean mold of rigid discipline. Cahill sees no merits in the treasures saved by the Benedictines, instead glossing over the important role they played in the preservation of Christendom.

All such Saints and Pontiffs, says Cahill in a phrase worthy of Bergoglio, exemplify placing “principles over people.”

Yearnings for paganism

As he presents Irish history, Cahill attacks and undermines Catholic orthodoxy at every turn. The best elements of the Faith are, to him, those practices he claims were adapted from paganism into Christendom. Whenever a barbarian people needed correction over clinging to barely Christianized versions of their pagan ways, the author laments the loss of this “nuance” from the past.

Despite his criticism of St. Augustine, it is worth noting that throughout his book Cahill revels in discussing the barbarian lack of sexual reserve. Not only does the author give inordinate attention obsessing in detail over this sordid subject, but he repeatedly condemns Catholic sexual morality in contrast to the pagan liberty.

Concluding thoughts

While disguising his attack against Traditional Catholicism and his yearning for a return to paganism as a book on Irish history, Cahill ends his work with a perhaps predictable attack against the West. We too, he claims, are like the Romans, so blissfully sunk in our decadence that we ignore the teeming huddled hordes massing at our borders ready to overrun our corrupt and decaying civilization. The West must open its borders and embrace the vital life-giving energy of open migration.

Confusingly, Cahill seems to think that the solution to the decay traditional Western civilization is to abandon our traditions even more. He has entirely confused the cause of our decay as the cure.

How Ireland Saved Civilization is a Trojan horse for resurrecting the myth of the Noble Savage. I cannot recommend this book to any Traditional Catholic.

Posted June 17, 2024

______________________