Book reviews

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Socialist Jew Exposes Flaws of Judaism

Book review of Anti-Semitism , Its History and Causes by Bernard Lazare

University of Nebraska Press, 1995, 208pp.

University of Nebraska Press, 1995, 208pp.

The author’s stated purpose is to make “an impartial study in history and sociology.” (Preface, p. 8) A reader immediately expects Lazare to thoroughly condemn Anti-Semitism, yet his express intent is to simply “account” for it by impartial analysis.

The author’s intent to fairly study this position so hostile to his own people makes a strong impression. From the perspective of our 21st century, where anything remotely approaching the specter of “hate towards Jews” is arbitrarily dismissed without any consideration, this attempt by a Jew to understand the grievances of the anti-Jew is a stimulating departure from the norm. Such a work serves to highlight the comparative intellectual decay of modern thought. It is doubtful how many today would be willing to entertain their opponents’ positions so seriously, let alone express sympathy with them as Lazare seems to do throughout his work.

He breaks down the causes for Anti-Semitism into categories of religion, economy and law, and establishes a surprising premise: The Jews are to blame for the complaints against themselves. Anti-Semitism is so universal throughout History and among differing peoples and circumstances that, Lazare concludes, the only constant factor contributing towards hostility to the Jews is the behavior of the Jews themselves. Lazare duly notes that this does not excuse Anti-Semitism nor does it pardon its excesses, but simply states “the Jews were themselves, in part, at least, the cause of their own ills.” (p. 8)

Exclusivity of the Jewish religion

The book then begins to weigh in earnestly on the study of Jewish history, thought and law, and examines how factors in these realms led to the Jews becoming an unfriendly nation. The Jews received the Law from God on Sinai, and thence forward treasured themselves as a chosen people. Nowhere could the Law of God be made subject to the “corruptible laws of man,” so Jews demanded autonomy. Often this autonomy was granted. Around the world Jews built retreats for themselves where their Law went unsullied by “gentile perversion.”

Along with this came the inevitable: a sense of superiority and a haughty pride. The ghettos of Europe were built at least in part by the Jews' own hands (p. 70). It is, to Lazare, no wonder that the Jew should be hated when he so scornfully hates all but his own people.

Jewish decrepitude

With the triumph of the rabbis, the Pharisees and the Talmud over the Jewish mind, Lazare asserts that the ostracism of the Jews was intensified. After their rejection of Christ and the Diaspora of 70 A.D., the Jews who did not convert to the Catholic Church clung all the more obstinately to their identity, isolating themselves through strict religious laws designed to avoid the least trace of “foreign contamination.”

Lazare criticizes the small-minded rabbis bickering over Talmud verses

Thus, while the Jew is naturally no more greedy than other races, Lazare argues, the peculiarity of the Jewish condition overwhelmingly led him to acquire the vice of usury. Throughout the book Lazare affirms that economic factors constitute a strong underlying force in Western resentment of Judaism.

Chauvinism & the myth of race

Throughout his work Lazare treats the Jews as a group but, in response to accusations against the Semitic race, he asserts that the theory of a pure race is false in and of itself. All races, he says, are the product of intermingling. Since ancient times, tribes and nations have shifted, conquered, intermarried and migrated. No modern peoples can claim pure heritage in the face of disparate world history.

What the Jews are, then, is a nation, a group of persons united by culture and ideals. Wherever the Jew has ceased to cling to his national identity, he has vanished. It is only the Jew’s pertinacious chauvinism that has kept him alive.

Naturally inclined to the Revolution

With the ghetto-bound money lender on the one hand, Lazare then analyzes the other pole of Judaism: the “enlightened” Jew. With the Talmud inculcating a thirst for material happiness, the Jew is naturally inclined to agitate against society’s status quo. The author admits that by nature the Jew played a strong role as the hotbed of anti-Catholicism (pp. 37, 51, 53, 74-76, 151-152) in the many revolutions that simmered over the centuries, and particularly in the French Revolution of 1789. (pp. 96-97)

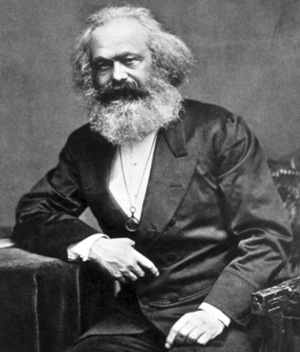

Bernard Lazare, above, condemns Judaism, but applauds Marx' communist ideas

To conclude, Lazare reveals himself to be what he hinted at throughout the book: a thoroughly radicalized revolutionary. In its closing pages this work extols the French Revolution, the Revolutions of 1838 and the Paris Commune of 1871. Lazare sings praises of Socialism, accepting the flawed Marxist theory of History without question.

To him reality is fundamentally the story of capital and class exploitation. Class warfare and the overthrow of Capitalism itself is the inevitable outcome, the pinnacle of all human history. The author believes it to be just around the corner. He wrote these lines in 1894. Today, this process is still in motion.

Thus, the true raison d'être for Lazare’s observations comes to light. Anti-Semitism is dismissed, for who can accuse a group of not integrating whilst putting up barriers to their assimilation? He is critical of the Jews insofar as they are accumulators of capital and insofar as they are close-minded victims of a defunct religion, which he considers the opiate of the people.

The Talmudic Jew is castigated, the atheist Jew is extolled. For Lazare, the true worth of the Jew is that he is raised in a nation that naturally breeds discontent. Those Jews who abandoned their faith became the most ardent revolutionaries, Marx, for example. Lazare’s confidence in the Communist ideals is boundless.

Thus, the author caps off the series of apparent contradictions, conducting the streams into one single river. He does not truly disparage the Jew, he disparages Jewish religiosity. He does not actually empathize with Anti-Semitism, he pines for the day these mobs will turn against their capitalist oppressors.

Anti-Semitism, Lazare concludes, is a contradiction working its own death: It castigates the Jew for refusing to integrate, whilst setting up barriers to that very assimilation; it stirs up mobs against the wealthy Jew without realizing the unhappy public will eventually turn against Anti-Semitism and Capitalism itself. The Jews must mobilize against Capitalism or they shall perish alongside the bourgeois.

Lazare’s book is a an interesting work for his frank critique of both Judaism and Anti-Semitism, but in his thinking he ultimately proves himself to be a radicalized product of the Revolution as it existed at his time.

- The Dreyfus Affair: A political crisis in France in 1884 where a French Jewish officer, Alfred Dreyfus, was convicted of selling military secrets to the Germans. Over time it became increasingly apparent that Dreyfus was a scapegoat, and the fact he was falsely convicted came to symbolize how Anti-Semitism was so rife in France.

Posted April 25, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |

Special Edition |