|

Book Reviews

Socialism and Distributism in Catholic Clothing

Patrick Odou

Book review on A Guildsman’s Interpretation of History, by Arthur J. Penty

(London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1920), 315 pp.

Although there are many shades of Socialism, deep down they all have the same color. They all have a problem with private property. Scientific Socialism (Communism) sought the “abolition of private property.” Fabian Socialism sought similar ends through “peaceful revolution.” Utopian Socialism has its “naturalist” distortions of property. National Socialism (Nazism) favored State control of property. The Russian communes eventually referred to anyone possessing more than two cows as an evil kulak (= a wealthy peasant, an oppressor). Even here in my own neighborhood (California), the Georgists (followers of Henry George) denied private property in land.

Above, cloth merchants in a window of Notre Dame, Paris |

Arthur Penty, known for his Guild Socialism, develops the thesis of this book using socialist misconceptions of Church doctrine, the Middle Ages, and more specifically, medieval guilds. As a result, Penty falls into one error after another while using Catholic terms and appealing to the Catholic world of the Middle Ages. In other words, he covers his socialist errors with Catholic clothing.

A socialist perspective of History

Historically, Penty sees Socialism and Communism as a good and private property as an evil. He presents this evil as initially created through the advent of currency:

“The first fact in history which has significance for Guildsmen is that of the introduction of currency [7th Cent. B.C.] … [which] created an economic revolution … by completely undermining the communist base of the Mediterranean societies” (p. 13).

This “communist base” was further destroyed by the development of the codex of Roman Civil Law, which he refers to as “the bible of the Devil” (p. 33).

Then, according to Penty, the communist traditions and spirit of the early Christians replaced the capitalist maxims of Roman Law and created the guilds: “It was the communistic spirit of Christianity that gave rise to the Guilds” (p. 37). But, the revival of Roman Law made private property return: “The revived study of Roman Law during the Middle Ages operated to undermine the communal relations of society and re-establish private property…” (p. 33).

So, due to Roman Law and an uncontrolled currency, there was another transition away from communism: a “transition from Medieval to modern society, from communism to individualism” (p. 308).

A Communist and anti-Catholic language

Penty, who is referred to in other works as a “sociologist, architect and Distributist,” was not a Catholic. Yet he develops his thesis based on his erroneous ideas of Catholic doctrine:

-“The Early Church continued the communistic tradition of the Apostles” (p. 35).

-“Although pure communism survives today in the monastic orders of the Roman Church, the communism of laymen did not last very long ….” (p. 36).

-“The appeal of Luther against the authority of the Pope had been to the traditions of the Early Church. Those traditions were communist, and it was because the early Christians despised wealth that they could approach God without the intervention of a priestly mediator … But when Luther alienated the peasants, he separated his gospel from any possible communist base…” (p. 152)

So, much like a modern progressivist or liberation theologian, Penty declares that this supposed communist tradition of the Early Church is the Catholic social doctrine that he imagines should be projected to every part of society.

According to Penty, the Church was unfaithful to the Gospel of Christ when it abandoned communist theory and communist practice:

“What happened with regard to usury happened also in respect to the institution of property. The communist theory and practice of the Church had been abandoned and the Church came to recognize the institution of private property.”(p. 156).

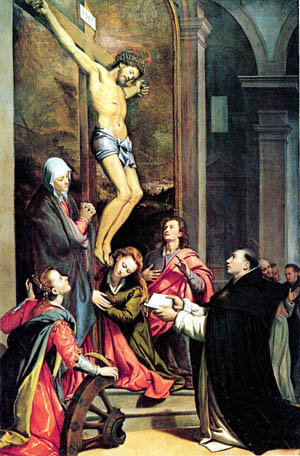

St. Thomas offers his writings to Our Lord |

To justify his absurd conception concerning the Church and private property, Penty attacks the integrity of St. Thomas Aquinas. He portrays the Saint as a venal intellectual who was not moved by the love of God, but by public pressure and fear:

“That confusion should exist in regard to the attitude of Christianity and the Medieval world towards property is, I am persuaded, due to the fact that St. Thomas Aquinas is regarded as representative of the Medieval point of view. It is insufficiently realized that his teaching about property was of the nature of a compromise intended to reconcile stubborn facts with the communistic teaching of the Gospel.

"In the thirteenth century, when he wrote, the Church was already defeated. It had failed in the attempt to suppress the revival of Roman Law, and the practical consequence of the failure was that landlordism was beginning to supplant communal ownership. To attack the institution of property as such was difficult, for the Church itself was implicated. It was already immensely rich. … In such circumstance, Aquinas apparently thought the only practicable thing to do was to seek to moralize property” [emphasis added] (p. 37).

Since Penty’s theses are now being presented to Catholics as a model for Distributism, it is not superfluous to remind them that such a thesis - that the Church should not have property - is condemned. The Syllabus of Errors clearly condemns the following: “The Church has no innate and legitimate right of acquiring and possessing property (Allocution Nunquam fore, Dec. 15, 1856; Encyclical Incredibili, Sept. 7, 1863; cited in The Syllabus of Errors by Pius IX, n. 26).

A Communist conception of society

With his warped conception of Church doctrine and the Middle Ages, Penty develops a socialist vision of the guilds. For, according to him, “it was the communistic spirit of Christianity that gave rise to the Guilds.” (p. 37).

The Author believes modern Trade Unions will lead to the creation of socialist guilds:

“In these days we recognize in the Trade Union Movement the first step towards a restoration of the Guilds. …they now control whole trades. They [Trade Unions] differ from them [Guilds] as industrial organizations only to the extent that, not being in possession of industry and of corresponding privileges, they are unable to accept responsibility for the quality of work done, and to regulate the prices. But these differences are the differences inherent in a stage of transition, and will disappear as the Unions trespass on the domains of the capitalist.” (p. 223)

Penty’s socialist doctrine seeks control not only of production but also of consumption:

“Hitherto Guildsmen have approached the problem from one particular angle. They have sought to transform the Trade Unions into Guilds by urging upon the latter a policy of encroaching control. This policy is good as far as it goes. But it is not the only thing that requires to be done. It is not only necessary to approach the problem of establishing Guilds from the point of view of the producer; it is equally necessary to approach it from the point of view of the consumer.” (p. 310).

At the end of a whole book about Christianity and the Middle Ages, Penty finally addresses (three pages from the end of the book) an obvious religious question. In order to establish the society he envisions, he asks if it would be necessary for reformers to return to the model of Christianity. He answers that this would be feasible only if Christianity is understood as the communist life that he imagines existed in the Early Church.

“Recognizing, then, that all societies are finally the expression or materialization of their dominant philosophy, and that when in the Middle Ages communal relationships …. were sustained by the teachings of Christianity, the question may reasonably be asked whether the policy we advocate does not imply a return to Christianity; must not reformers return to the churches? The answer is that this would be the case if the churches taught Christianity as it was understood by the Early Christians. But such is not the case.” (p. 309).

So, as with all communists, Penty has a materialist philosophy. For him, as well as for Karl Marx, Civilization is not a consequence of religious principles applied to social life, but simply “the development of the material accessories of life,” (p. 13).

A reading of Penty’s book brings to mind the old list of Communist goals – abolish private property; property should be collective and run by a commune, workers assembly, guild or soviet; a communist conception of work; a materialist philosophy of History, etc. Everything is reminiscent of the outdated pre-perestroika line of Communism.

The Catholic Worker (logo above) promotes Penty's books. Below, co-founder Dorothy Day protests against war

|

So, why analyze his work now?

Present day interest in Penty’s work

Today, Penty’s work still raises interest in some segments of English and American communist movements, union workers, and also some Catholic movements represented by, for instance, The Catholic Worker. At present, as far as I know the only place to purchase A Guildsman’s Interpretation of History is from The Catholic Worker Bookstore for $25. The Catholic Worker - founded by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day back in the 1930s - is a well-known periodical and movement of the ‘Catholic Left’ which promotes “communism” and a “pacifist revolution” for “worker-ownership of the means of production and distribution,” and “favors the establishment of a Distributist economy” (www.catholicworker.org/dorothyday/daytext.cfm?TextID=519).

But there is something else. We are witnessing an attempt of a restoration of “Christendom” by some so-called conservative and traditionalist Catholics. It is indeed a curious Catholic society that one can envision based on the theses of Penty and his notions of how to distribute property. So here we have Arthur Penty, who by the way was also the author of The Distributist Manifesto, as one of the principal minds inspiring the new Distributist model that is being advertised in many places today.

In my opinion, this new fashion of promoting Penty and associates without any reserve or warning should be carefully examined. All the more so since some well-known leftist Catholic movements are joyfully applauding these conservative and traditionalist Catholics. For instance, an article from Casa Juan Diego, a major website of The Catholic Worker network, rejoices;

“Good news to all who have searched used bookstores to no avail looking for titles by Vincent McNabb, Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, Arthur Penty and others that Peter Maurin recommends in his Easy Essays. Peter [Maurin] enthusiasts need look no further, for all those mentioned are in the IHS [Press] catalog .…” (www.cjd.org/paper/roots/rMcnabb.html).

Given the communist theses of the book A Guildsman’s Interpretation of History, it seems to me that it doesn’t hurt to be vigilant regarding this new out-of-date fashion - Distributism.

Posted on September 2, 2004

Related Topics of Interest

A Torrent of Pros and Cons on Eric Gill, a Founder of Distributism A Torrent of Pros and Cons on Eric Gill, a Founder of Distributism

Other Moral Pearls of Eric Gill Other Moral Pearls of Eric Gill

Eric Gill: the Pedophile Founder of Distributism Eric Gill: the Pedophile Founder of Distributism

Eric Gill, a Precursor of Vatican II Eric Gill, a Precursor of Vatican II

A Distributist Manifesto Strongly Spiced With Communism A Distributist Manifesto Strongly Spiced With Communism

|

Book Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|