|

The Saint of the Day

St. Melania the Younger – December 31

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

Melania was born in 383, daughter of Valerius Publicola, a very noble family of Roman Senators. At age 14 she wanted to consecrate herself to God, but her parents married her to Valerius Pinianus, who was only three years older than she. With this marriage two branches of the greatest families of the Roman Empire united, thus making the richest existing patrimony of the Roman aristocracy.

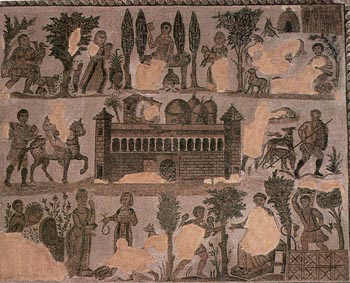

St. Melania the Younger, benefactress and builder of many monasteries and convents

|

After having two sons who died at an early age, Valerius and Melania made the decision to adopt a life of chastity. Melania then resolved to donate her fortune to church institutions and the poor so that she could dedicate herself to a life of prayer and study of the saints. But it took many years for her to disperse of her fortune, qualified by one author as prodigious.

Indeed, besides her jewelry, silver and precious art, she possessed large lands called latifundia in Italy, Sicily, Gallia, Spain, Proconsular Africa, Numidia, Mauritania, Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Her fortune was so massive that one palace in Rome could not be sold because no buyer with sufficient money to purchase it could be found. Even the Senate remarked on her sale of properties as an inordinate waste, but the Saint remained firm in her purpose, attaining it after many years.

With the money from the sales, she built convents and monasteries, protected the poor, gave donations to the churches and rescued prisoners. Her business affairs caused the Saint to travel a great deal, and she chose to reside in places where the Bishops were known for holiness and knowledge of the Scriptures. In this way she came into contact with the great saints of her time, like St. Augustine.

After she had carried out the “work of Martha,” as she called her concern with earthly goods, she dedicated herself to the “work of Mary,” her desire of many years. She retired to a convent in Jerusalem, wore sackcloth as penitent dress, and dedicated herself to prayer, fasting and the study of Scriptures.

She wrote greatly, doing the work of a scribe since she had a good knowledge of Latin and Greek. She encouraged the night prayer of the Divine Office and was the spiritual director of many convents for women.

St. Melania died in Jerusalem on December 31, 439. Her life was minutely recorded by her adoptive son and spiritual disciple Gerontius. She was considered one of the great personages of her time and earned a great eulogy by St. Jerome, who pointed to her as a model for his feminine followers.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

These data about St. Melania can only be duly understood when we take into consideration the way wealth was distributed in the Roman Empire. Official historians like to praise the ancient civilizations, describing the Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Indian, Chinese and Japanese civilizations as marvelous. But they leave certain topics in oblivion as, for example, the role of the middle class and the welfare of the workers.

In most of these civilizations there was no middle class as we understand it today and there were no benefits for the workers because almost all workers were slaves. The majority of the inhabitants of Rome and the Roman Empire was comprised of slaves. The much-praised juridical sense of the Romans was remarkable, I agree, but what happened is that the greater part of the population made up of slaves was situated outside of the law. The law applied only to a minority.

A mosaic glorifying the extensive estates of the Roman nobles

|

A similar thing happened with the distribution of riches. In the pagan world, we see the accumulation of fabulous fortunes, completely disproportionate to the human capacity to enjoy them or offer more dignity to their owners. I do not censure an ordinate luxury. I admit that a man can have several palaces. But when someone has so many palaces that he cannot even know them all, much less use them, when he has so many lands that he does not have time to administer them, it follows that there is a disproportion between his goods and his person. This constitutes, therefore, a phenomenon of bad distribution.

Let us take, for example, a Roman who had a medium fortune – Cicero, who was a simple lawyer. The inventory of his goods reveals that he was a nabob, a veritable magnate. In his letters and documents he acknowledges that his patrimony was so large that he did not even know the greater part of what he had.

Well, St. Melania was the heiress of a fabulously wealthy family, whose patrimony spread out over the whole Roman Empire. What she did is one of the true beauties of wisdom of the Church: She was a noble who did not just want to reduce her fortune to a human proportion, but chose to completely disperse all her belongings in order to practice poverty.

This was not as easy for her as it was for St. Francis of Assisi because St. Francis possessed only the tunic he was wearing. He took off his tunic in the central piazza of Assisi, handed it to his astonished father Piero Bernardone, and said: “Now, I can truly say: my Father, who art in Heaven.” He went to the Bishop of Assisi, who wrapped his cloak around the young man. For Francis, the matter of poverty was resolved: He had given everything he had: his tunic. So, ridding himself of his worldly goods was an action that was quickly executed. St. Melanie could not do this so easily.

She had a stupendous patrimony: precious works of art, riches of all types, palaces, lands, etc. She could not squander that fortune foolishly just to be rid of it because she had to give an account to God for it. No matter how great her desire to be a religious, she had to sell her goods and properties in an orderly way and use the gains appropriately. Only after everything was sold and distributed could she in good conscience enter a convent.

A 17th century woodcut of St. Melania, honored as one of the greatest donors of the Church

|

Why did she not give everything to her relatives? It is insinuated in the narrative that she did not have relatives whom she could trust with her fortune; otherwise she would not have been obliged to engage in that enormous task herself. Here we find a scene that is never encountered among pagan peoples: a grand lady from an illustrious family struggling to be poor. She strove with a heroic perseverance for many years to sell all that she had and invest the gains well.

She ended by selling her whole fortune and she retired to a convent. Here another facet of her soul appears. After divesting herself of everything, she was enshrined in dignity; she became the superior of the convent. After leading the destruction of her patrimony, she became a spiritual leader; she built the spiritual patrimony of many other souls. She directed souls and counseled numerous convents. She oriented a large family of souls in various places. Then, after years and years of the actual practice of poverty, she delivered her soul to God.

She spent her life dispersing the treasures that so many collect, and collecting the treasures that so many disperse. She was not thirsty for social position, money and comfort; she was thirsty for souls; she wanted to bring souls to Our Lord Jesus Christ through Our Lady.

She also sought the acquaintance of saints. She sought out places where saints were living so that she could benefit from their counsels. Thus, she had the privilege of conversing with St. Augustine. She was praised by St. Jerome. To be praised by a saint is a great thing; to be praised by St. Jerome is a very great thing.

St. Jerome had the genius to make polemics, which implies seeing the bad side of people in order to destroy the enemies of the Church. As a side effect of this vocation, he saw the defects of each person with great lucidity. So, for him to praise the severe, rigorous, genuine and coherent virtue of St. Melania was a rare thing. For her it was a great glory to have her life complimented by St. Jerome because she was judged by a very rigorous judge. If he, in his severity, found her virtue to be of perfect gold, it was because her soul was fully prepared to appear before God.

The tomb of St. Melania in Jerusalem, where she died on December 31 in the year 439

|

In our epoch, what should be said about the lives of saints like St. Melania? On one hand, they edify us greatly; but, on the other hand, they require a commentary. Her example should not make us think that to be grand lady and the owner of many goods is opposed to sanctity. This is false. A grand lady who possesses many goods must give alms. If she has superfluous goods and can still maintain her social position and dignity of status without some of those goods, she should give from them. But a grand lady can become a saint even if she keeps them and uses them well.

So, we should not believe that a saint cannot be the owner of great properties and riches. St. Melania’s gesture was beautiful, but she could also have become a saint if she had kept her fortune and maintained a detachment from earthly things. This is why we have many saints who were queens and kings, that is, persons who, like St. Melania, had great riches.

She received a different call from grace to embrace another form of life. She obeyed and became a saint. She became a religious woman, entering a more perfect state of life, and until today her life edifies us. This is the glory of a saint.

When Victor Hugo was elected to enter the French Academy of Letters – whose members are called immortals because their glory remains forever – he made this comment to someone who was praising his new title: “I will not have an immortal glory. After a time, no one will care about my work. The true glory is the glory of the Catholic Saints, which never fades.”

He was right. Some time ago I read that the books of Hugo were being sold by the pound in Paris. The glory of St. Melania, however, remains forever. She died in the 5th century, and in the 20th century we are still praising her here in Brazil, a country that did not exist when she was alive. Her glory will endure so long as the world exists.

|

|

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|