|

The Saint of the Day

St. Erlembald - August 3

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

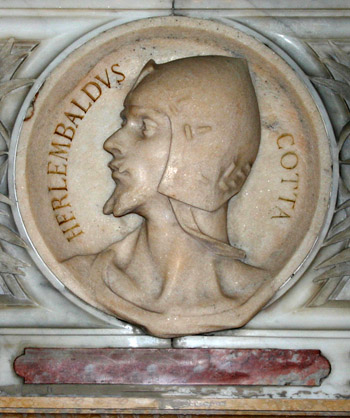

Erlembald or Eriembaldo was a Milanese Lord, a fearless knight of Christ who died in 1075, belonged to the illustrious Milanese family Cotta and became a captain of arms in his youth. Although not a robust man, he was courageous as a lion. Very wealthy, his Milanese Palace rivaled in magnificence the castle of a king. However, his heart was not turned to the goods of earth, but rather to God.

St. Erlembald in the basilica of San Calimero, Milan |

When he returned from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, he announced his intent to enter the monastic life. However, he was counseled not to take this step by the deacon St. Arialdo and to fight for the Church as a lay knight instead. He pointed out to Erlembald how the Church was going through an hour of darkness with the spread of simony and impurity in the clergy, abuses protected not only by ecclesiastical authorities but also the civil powers.

Erlembald travelled to Rome to confer with Pope Alexander II, who counseled him to remain in the lay state and return to Milan to help Arialdo combat the enemies of Christ, even to the shedding of his blood, if necessary. In the name of St. Peter, the Pope gave him a standard for the warrior to carry to repress the furor of the heretics. This banner was faithfully borne by the Saint for 18 years.

This illustrious Lord always appeared in public richly dressed, appropriate to his dignity, followed by an imposing retinue. When he walked through the streets of Milan, the people followed to pay him homage. If he noticed a beggar or a sick person on the street, he would point him out to one of his servants, who would bring the unfortunate person to the palace where the noble would personally attend him. He was as charitable as he was devoted to the interests of the Church.

His heart was so upright that St. Arialdo used to say of him: “Alas! Save for Erlembald and Nazarius, I find scarcely someone who does not try to persuade me under a false sense of discretion to remain silent so that the simoniacs and adulterers can freely commit the works of the Devil.”

For 10 years Duke Erlembald fought for the cause of God, often conflicting with Archbishop Guido of Velate. In 1059, St. Peter Damian was sent to Milan as a papal legate and demanded that Archbishop Guido and his clergy take an oath condemning simony. To retain their places, they took the oath, but when a see became vacant, the Archbishop himself accomplished a simoniac arrangement.

Erlembald went to Rome and returned with a letter excommunicating the Archbishop. Furious, Guido called together an enormous multitude in the Church. There, holding the condemnatory Papal Bull in his hand, he stirred up the people against Arialdo and Erlembald. “Never,” he said, “has this city obeyed the Church of Rome. Let us do away with these wretched persons who want to steal our age-old freedom.”

The populace shouted: “Kill them now!” And they fell upon the two servants of God who were also present in the Church: the clergy over Arialdo and the laity over Duke Erlembald.

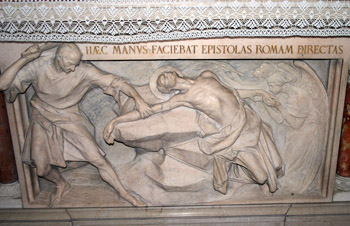

The mutilation and murder of the deacon St. Arialdo |

Arialdo was gravely wounded, but Erlembald defended himself so well that none could come near him. Arialdo recovered and fled to Rome. On his way, however, he was betrayed by a priest of the corrupt Archbishop and delivered to his partisans who dragged Arialdo to a desert place and killed him after first mutilating him. Erlembald went to recover the body of his friend and, followed by a large multitude, deposited it in St. Celso’s Church in Milan in 1067.

The next year, Archbishop Guido reconciled with the Holy See. But, in 1069 he decided to renounce his see and choose his successor, Godfried of Castiglione, his secretary. The peasants of Milan rejected the choice with horror. Seeing his plan frustrated, Guido tried to reach an accord with Erlembald. The Duke, however, judged that there could be no pardon for that guilty Prelate and locked him in the Monastery of St. Celso.

Fearing for his life, Godfried sought refuge in the fortified Castle of Castillon. The Milanese people pursued him closely, but, to save him, Godfried’s partisans started a fire in the city to divert their attention. The people retreated and Godfried would have been safe if Erlembald had not entered the siege carrying the Standard of St. Peter, attacking the Castle with such force that he destroyed the enemy. Pope St. Gregory VII named a new Archbishop for Milan and encouraged the Duke to continue to defend Milan, the see of St. Ambrose.

Erlembald continued to fight strongly to guarantee the rights of the legitimate Archbishop chosen by the Pope. His enemies, unable to conquer him in battle, decided to have recourse to murder. One day when the Duke of Milan was talking with the people, his enemies fell upon him. Although he heroically resisted, he was vastly outnumbered and defeated. He was holding the Standard of Sr. Peter when he succumbed to the blows of the assassins.

His death was mourned by all faithful of the Roman Church as far away as the countryside of England. The people could not be consoled at the loss of the brave Knight of Christ, as St. Gregory VII called him. Shortly afterward, Blessed Urban II placed Erlembald among the number of the Saints.

(Abbé Profilai, The Military Saints)

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

This is one of the most beautiful selections we have been asked to comment on. This biography is so rich in data that perhaps the commentary may be a little long. Let us analyze what happened in the life of this Saint.

A medieval illustration of simnony - the selling of church offices |

At that time Italy was divided into two currents: one obeyed the Roman Church, the infallible see of St. Peter; the other current was infected with doctrinal heresies and had very bad customs, among them the practice of simony.

Simony is the act of selling an ecclesiastical position. For example, when an Archbishop or Bishop would name a vicar or a canon to an ecclesiastical office, instead of choosing the more worthy man for the position, he would auction it off and give the position to the one who offered the highest price.

In the Middle Ages, since the generosity of the people was great, such positions were very profitable. It was possible to make a lot of money in an ecclesiastical post, especially for a dishonest man. So, a great number of ambitious men disputed for those posts. Obviously, this led to great corruption, because when an individual without a vocation for the office purchases a post, then he does not fulfill the obligations of that office and enters into other forms of corruption, such as impurity. So, free reign was given to corruption.

Further, when a man purchases a position, he does so to make money. Hence, after he has it, he does anything – sells relics and objects of devotion, steal properties, degrade the cult etc. – in order to make a profit. At that time, the consequences of these cases of simony had a long reach in society: A multitude of persons depended on those ecclesiastical positions held by dishonest men.

The Virgin and Child at the Monastery of Cluny |

Since we know about how the Secret Forces and the Revolution work, we see that the situation of this time was a preparation for the Revolution, with a current of corrupted persons placed in important ecclesiastical posts so that simony and impurity would dominate the Church and influence all of Christendom.

In this dark situation, however, something good appeared in the Church. It was the Order of Cluny, which bloomed as a branch of the Benedictine Order. Cluny represented the hardline, a rigorism in maintaining morals and good customs. At its head was the Holy See, whose major exponent was St. Gregory VII. He was preceded by a series of ultramontane Popes and Saints who combated with all their force the heresies, simony and corruption of that time.

Sometimes the laymen also favored simony because they could purchase ecclesiastical positions for members of their families or for their personal financial benefit. At times, the feudal lords, who had the right to veto candidates for ecclesiastical positions, would receive money to name or approve a certain individual for a post. So, for them, those offices were a source of income. In this way, a great number of feudal lords came to support simoniac and corrupted priests. Thus, we find a lay development of that religious corruption taking place on the political terrain.

The Popes combated and deposed those simoniac Bishops, but often the Bishops refused to abandon their posts and were supported by the feudal lords who favored the corruption. It was natural that the good feudal lords were faithful to the Pope and opposed the corruption.

The religious fight spilled over, then, into the political terrain and, from the political front, to the military terrain. To expel the bad Prelates and obey the Popes, the good feudal lords maintained personal armies. In this way, a war of small proportions was established all over Italy, which had a great number of small principates and bourgeois republics, each with its own internal war. The parties of one region communicated with their cohorts in other areas and supported them, further complicating the situation.

At the time that the current of Cluny was making an effort to reform the Church to rid her of these problems, two Saints with an extraordinary wingspan appeared in Milan: Blessed Arialdo, a clergyman who fought fiercely against simony with religious weapons, and Duke Erlembald in the civil terrain.

The names – Erlembald and Arialdo – reveal a close relation to the Germanic peoples at the time of the invasions. Probably they were Lombard names, since the Lombards occupied the area of Milan and settled there.

Continued

|

|

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|