Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CI

Contested Boundaries & ‘Bridging the Gap’

The Liturgical Movement set out to reframe the issue [of “active participation”] so that the age-old clergy-laity distinction would be seen as a problem, one that could only be rectified by a radical reform to give the laity more power and control in the liturgy. This Marxist-style dialectic was simply an assumption of collective clerical guilt for having “dominated” the liturgy and “monopolized” all the action.

Fr. Yves Congar, OP, one of the most influential theologians at Vatican II, put it this way: “For more than 15 centuries now, Rome has striven to monopolize ‒ yes to monopolize ‒ all the lines of direction and control. And has succeeded!” (1)

Fr. Yves Congar, OP, one of the most influential theologians at Vatican II, put it this way: “For more than 15 centuries now, Rome has striven to monopolize ‒ yes to monopolize ‒ all the lines of direction and control. And has succeeded!” (1)

He complained that “the hierarchical priesthood has, as it were, taken over everything” (2) and treated the non-ordained as if they were not fully members of the Church by their Baptism. That was the founding narrative of the Liturgical Movement, first introduced by Dom Lambert Beauduin in 1909, and became the blueprint for all subsequent reforms involving “active participation” of the laity in the liturgy and life of the Church. It is still believed today and is used as the ongoing justification for “active participation.” (3)

The solution envisaged was to set in motion a systematic encroachment of the priest’s ministerial role in favor of lay “active participation” as a means of “redressing the balance” and restoring “justice” to the laity for having allegedly suffered at the hands of the clergy for so many centuries.

Congar’s dynamite

This Marxist rationale was certainly the perspective that informed all of Fr Congar’s writings, and earned him the censorship of the Dominican Order and the Vatican in the 1950s. (4) But in 1954, he gleefully recorded in his diary that if he was banned from writing, he could continue his opposition to “the system” (by which he meant the Church’s Constitution, doctrine, governance and rites) in his lectures.

He said that one of these lectures would put “true dynamite under the chairs of the scribes!” – a reference to the Roman authorities who had disciplined him. This suggests a way of thinking that is more about personal revenge than a concern for justice.

He said that one of these lectures would put “true dynamite under the chairs of the scribes!” – a reference to the Roman authorities who had disciplined him. This suggests a way of thinking that is more about personal revenge than a concern for justice.

Fr. Congar considered it “a matter for rejoicing” that in the 1951 Pascal Vigil the priest is made to sit and listen while someone else (including a layman) reads the Scriptures, because Congar realized the explosive potential of this breach with a 1,000-year-old tradition: It marked the first official step in the process of dethroning the priest from his exalted position in the liturgy.

The revolutionary undertones of this reform can be gleaned from Congar’s statement:

“The laity will not be re-established in the fullness of its quality as the Church’s laity until the spirit of that small Easter reform of 1951 shall have been extended to all the spheres where it is relevant”. (5)

The spirit of the Bolshevik Revolution

What spirit he had in mind was later revealed when, in an off-guard moment, he declared triumphantly that with Vatican II “the Church has peacefully accomplished its own October Revolution.” (6)

The metaphor could not be more appropriate in terms of cataclysmic legacy: The 1917 Revolution led to 70 years of devastation, beginning with regicide and the massacre of Russia’s Romanov dynasty, children included; Vatican II ended the monarchical structure of the Church with the Pope as “King,” triggered an era of ecclesiastical mayhem and handed victory to the Catholic

Bolsheviki – of whom Congar himself was a prime example.

The metaphor could not be more appropriate in terms of cataclysmic legacy: The 1917 Revolution led to 70 years of devastation, beginning with regicide and the massacre of Russia’s Romanov dynasty, children included; Vatican II ended the monarchical structure of the Church with the Pope as “King,” triggered an era of ecclesiastical mayhem and handed victory to the Catholic

Bolsheviki – of whom Congar himself was a prime example.

As for “all the spheres where it is relevant,” this became evident after said Bolsheviki won the day at Vatican II. With the introduction of Communion in the hand, it was not long before the laity were invested with ministry at the altar, simulating the work of the external priesthood.

There are now lay Eucharistic Ministers, and lay Presiders of priestless Communion services; lay Lectors (of both the Epistle and the Gospel) and lay preachers of the homily; lay ministers of sacramentals, e.g., to bless throats and administer ashes; lay Presiders of weddings and funerals; lay Pastoral Associates and lay Chaplains for hospitals and schools; lay Parish Administrators and even lay Chancellors of dioceses – to name some of the most egregious examples.

‘Equal is as equal does’

According to the liturgical reformers’ new theology, the primacy of the priest’s activities in the Mass must give way to an equality of action of the assembled faithful who are all priests, just as much as he is. If we follow their chain of reasoning by which they arrived at their theory of lay “active participation,” we will find a well-worn pattern of misdirection: starting with a correct premise drawn from Scripture and twisting its meaning to produce a conclusion at odds with Catholic teaching.

There is a consensus among the members of the Liturgical Movement that the New Testament (1 Pet 2:5, 9) establishes the basis for lay “active participation.” Here St Peter declares that Christians, by reason of their baptized status, constitute “a holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices.” We must keep in mind that the Apostle, in describing the priestly status of all the faithful, was speaking in a purely figurative sense.

Let us look at how the Church up to the middle of the 20th century has understood this.

The clarity of pre-Vatican II times

The Council of Trent explained clearly that the visible and external priesthood belongs to the ordained ministers who mediate between man and God, while the laity are endowed through Baptism with an “internal priesthood” which enables them to “offer up spiritual sacrifices on the altar of their hearts.” (7)

The only true participation of the laity present at Mass consists, therefore, in uniting the interior homage of their heart to the visible rite performed by the priest. This distinction was understood by all, and was incarnated in the liturgical rites, vestments, governance and architecture of pre-Vatican II churches which were uninfluenced by the new “theology of the liturgical assembly.”

The only true participation of the laity present at Mass consists, therefore, in uniting the interior homage of their heart to the visible rite performed by the priest. This distinction was understood by all, and was incarnated in the liturgical rites, vestments, governance and architecture of pre-Vatican II churches which were uninfluenced by the new “theology of the liturgical assembly.”

Although the character imprinted on the Christian soul by the Sacrament of Baptism causes lay people to enter into the internal priesthood mentioned by the Council of Trent, it does not make them participate in the external priesthood. Nor does it endow them with a right to active participation in the Church’s rites. There is, therefore, only an analogy between the priesthood of the layman and that of the ordained minister, which is the only true priesthood.

However, Trent’s teaching was first rendered incoherent by Pius XII who, as we have seen earlier, yielded to the demands of the liturgical reformers, and made “active participation” of the laity an integral part of the Roman Missal.

This means that the laity’s “internal” priesthood was, as it were, turned inside out and made “external,” causing confusion in anyone trying to understand the essential binary distinction between the ordained and lay states. Ever since then, the boundaries between the clergy and laity have become increasingly porous.

The ‘universal priesthood’ as promoted by Vatican II

We can locate the reason for this confusion in the wording of Lumen Gentium §10 which, upon close inspection, turns out to be a façade for the “new theology” and introduces ambiguity, uncertainty and confusion:

“Though they differ essentially and not only in degree, the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood are nonetheless interrelated: Each in its own way shares in the one priesthood of Christ”.

“Though they differ essentially and not only in degree, the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood are nonetheless interrelated: Each in its own way shares in the one priesthood of Christ”.

The sentence may start by reiterating a valid statement, but this is hastily batted to one side to draw the focus of attention away from the orthodox teaching and redirect it towards a concept of the priesthood with very blurry edges.

The words “though” and “nonetheless” introduce a modification to the traditional doctrine, making it seem less true, less worthy of credibility. What is meant by “interrelated” is left obscure, open to opinion and to the imagination of creative liturgists to interpret its practical application in the Church. And the reference to all promiscuously sharing Christ’s priesthood placed clergy and laity on the same level, making it difficult to distinguish between the two.

But, as priests and lay people belong to two mutually exclusive ontological categories, the argument contained in §10 is self-contradictory because it starts by saying they are essentially different, and then implies that they are really one and the same essence.

It is now evident that §10 was a linguistic sleight of hand to mystify the Council Fathers and manipulate them into signing a document that would, as history has shown, be used to undermine the priesthood. It was an attempt to sidetrack the Church’s perennial teaching on the ministerial priesthood by raising a false issue about lay “active participation,” and constitutes one of the many intellectually dishonest tactics typically used in the Council documents to deceive the faithful into accepting an unorthodox teaching.

But what was the precise intention of the corruption of language embedded in §10 and its use of weasel words to distort the truth? Romano Amerio, who was himself a peritus (expert) at Vatican II and familiar with the thinking of the progressivist theologians, commented:

“The new theology revives old heretical doctrines, which came together to produce the Lutheran abolition of the priesthood, and disguises the difference that exists between the universal priesthood of baptized believers and the sacramental priesthood, which is proper to priests alone.” (8)

Continued

Yves Congar in 1965 at a Milan conference

preaching lay participation

He complained that “the hierarchical priesthood has, as it were, taken over everything” (2) and treated the non-ordained as if they were not fully members of the Church by their Baptism. That was the founding narrative of the Liturgical Movement, first introduced by Dom Lambert Beauduin in 1909, and became the blueprint for all subsequent reforms involving “active participation” of the laity in the liturgy and life of the Church. It is still believed today and is used as the ongoing justification for “active participation.” (3)

The solution envisaged was to set in motion a systematic encroachment of the priest’s ministerial role in favor of lay “active participation” as a means of “redressing the balance” and restoring “justice” to the laity for having allegedly suffered at the hands of the clergy for so many centuries.

Congar’s dynamite

This Marxist rationale was certainly the perspective that informed all of Fr Congar’s writings, and earned him the censorship of the Dominican Order and the Vatican in the 1950s. (4) But in 1954, he gleefully recorded in his diary that if he was banned from writing, he could continue his opposition to “the system” (by which he meant the Church’s Constitution, doctrine, governance and rites) in his lectures.

Congar's dream achieved: Francis sits & the laity read from the pulpit in St. Martha's Chapel

Fr. Congar considered it “a matter for rejoicing” that in the 1951 Pascal Vigil the priest is made to sit and listen while someone else (including a layman) reads the Scriptures, because Congar realized the explosive potential of this breach with a 1,000-year-old tradition: It marked the first official step in the process of dethroning the priest from his exalted position in the liturgy.

The revolutionary undertones of this reform can be gleaned from Congar’s statement:

“The laity will not be re-established in the fullness of its quality as the Church’s laity until the spirit of that small Easter reform of 1951 shall have been extended to all the spheres where it is relevant”. (5)

The spirit of the Bolshevik Revolution

What spirit he had in mind was later revealed when, in an off-guard moment, he declared triumphantly that with Vatican II “the Church has peacefully accomplished its own October Revolution.” (6)

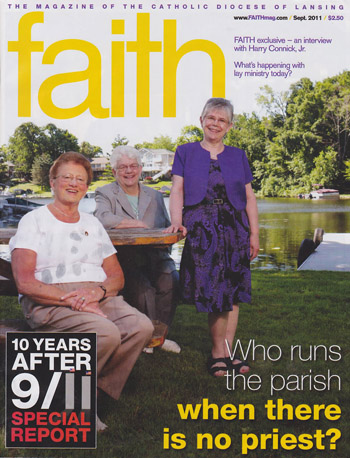

Laity have become ‘co-workers’ with priest under multiple titles

As for “all the spheres where it is relevant,” this became evident after said Bolsheviki won the day at Vatican II. With the introduction of Communion in the hand, it was not long before the laity were invested with ministry at the altar, simulating the work of the external priesthood.

There are now lay Eucharistic Ministers, and lay Presiders of priestless Communion services; lay Lectors (of both the Epistle and the Gospel) and lay preachers of the homily; lay ministers of sacramentals, e.g., to bless throats and administer ashes; lay Presiders of weddings and funerals; lay Pastoral Associates and lay Chaplains for hospitals and schools; lay Parish Administrators and even lay Chancellors of dioceses – to name some of the most egregious examples.

‘Equal is as equal does’

According to the liturgical reformers’ new theology, the primacy of the priest’s activities in the Mass must give way to an equality of action of the assembled faithful who are all priests, just as much as he is. If we follow their chain of reasoning by which they arrived at their theory of lay “active participation,” we will find a well-worn pattern of misdirection: starting with a correct premise drawn from Scripture and twisting its meaning to produce a conclusion at odds with Catholic teaching.

There is a consensus among the members of the Liturgical Movement that the New Testament (1 Pet 2:5, 9) establishes the basis for lay “active participation.” Here St Peter declares that Christians, by reason of their baptized status, constitute “a holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices.” We must keep in mind that the Apostle, in describing the priestly status of all the faithful, was speaking in a purely figurative sense.

Let us look at how the Church up to the middle of the 20th century has understood this.

The clarity of pre-Vatican II times

The Council of Trent explained clearly that the visible and external priesthood belongs to the ordained ministers who mediate between man and God, while the laity are endowed through Baptism with an “internal priesthood” which enables them to “offer up spiritual sacrifices on the altar of their hearts.” (7)

Pre-Vatican II Mass: Only ecclesiastics on the altar

Although the character imprinted on the Christian soul by the Sacrament of Baptism causes lay people to enter into the internal priesthood mentioned by the Council of Trent, it does not make them participate in the external priesthood. Nor does it endow them with a right to active participation in the Church’s rites. There is, therefore, only an analogy between the priesthood of the layman and that of the ordained minister, which is the only true priesthood.

However, Trent’s teaching was first rendered incoherent by Pius XII who, as we have seen earlier, yielded to the demands of the liturgical reformers, and made “active participation” of the laity an integral part of the Roman Missal.

This means that the laity’s “internal” priesthood was, as it were, turned inside out and made “external,” causing confusion in anyone trying to understand the essential binary distinction between the ordained and lay states. Ever since then, the boundaries between the clergy and laity have become increasingly porous.

The ‘universal priesthood’ as promoted by Vatican II

We can locate the reason for this confusion in the wording of Lumen Gentium §10 which, upon close inspection, turns out to be a façade for the “new theology” and introduces ambiguity, uncertainty and confusion:

Priestless parishes are becoming more common with laypersons assuming almost all priestly duties

The sentence may start by reiterating a valid statement, but this is hastily batted to one side to draw the focus of attention away from the orthodox teaching and redirect it towards a concept of the priesthood with very blurry edges.

The words “though” and “nonetheless” introduce a modification to the traditional doctrine, making it seem less true, less worthy of credibility. What is meant by “interrelated” is left obscure, open to opinion and to the imagination of creative liturgists to interpret its practical application in the Church. And the reference to all promiscuously sharing Christ’s priesthood placed clergy and laity on the same level, making it difficult to distinguish between the two.

But, as priests and lay people belong to two mutually exclusive ontological categories, the argument contained in §10 is self-contradictory because it starts by saying they are essentially different, and then implies that they are really one and the same essence.

It is now evident that §10 was a linguistic sleight of hand to mystify the Council Fathers and manipulate them into signing a document that would, as history has shown, be used to undermine the priesthood. It was an attempt to sidetrack the Church’s perennial teaching on the ministerial priesthood by raising a false issue about lay “active participation,” and constitutes one of the many intellectually dishonest tactics typically used in the Council documents to deceive the faithful into accepting an unorthodox teaching.

But what was the precise intention of the corruption of language embedded in §10 and its use of weasel words to distort the truth? Romano Amerio, who was himself a peritus (expert) at Vatican II and familiar with the thinking of the progressivist theologians, commented:

“The new theology revives old heretical doctrines, which came together to produce the Lutheran abolition of the priesthood, and disguises the difference that exists between the universal priesthood of baptized believers and the sacramental priesthood, which is proper to priests alone.” (8)

Continued

- Yves Congar, My Journal of the Council, Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2012, p. 7.

- “What a matter for rejoicing it is that, in the Pascal Vigil service as restored in 1951, the celebrant listens to the prophecies read by another minister, without reading them privately himself.” Yves Congar, Lay People in the Church: A study for a theology of laity, London: Chapman, 1957, p. 435.

- Many progressivist commentators use frankly Marxist expressions to keep the Liturgical Revolution going, e.g. ex-priest Paul Lakeland claimed that the Catholic laity are the victims of “structural oppression” caused by collective clericalism: The Liberation of the Laity: In Search of an Accountable Church, New York: Continuum, 2003, p. 194; and Fr. Paul Philibert, OP, a follower of the noted Dominican theologians Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar, wrote that the Church must combat “the clericalizing tendencies of the ministerial elites”: The Priesthood of the Faithful: Key to a Living Church, Liturgical Press, 2005, p. 16.

- From 1947 to 1956 Congar's writings were subjected to stringent censorship because of his unorthodox theological opinions and his involvement in ecumenical activity with the Protestants. When, for example, he published Vraie et Fausse Réforme dans l'Église (True and False Reform in the Church) in 1950, the Vatican banned any further printing of the book and any translations of it into foreign languages.

- Yves Congar, Lay People in the Church: A study for a theology of laity, London: Chapman, p. 436.

- “L’Église a fait pacifiquement sa Révolution d’octobre ‒ Yves Congar, Le Concile au jour le jour: Deuxième session (The Council day by day, second session), Paris: Cerf, 1964, p. 115.

- Catechism of the Council of Trent, translated by McHugh and Callan New York, 1934, p. 330. The Council of Trent stated: “But as Sacred Scripture describes a twofold priesthood, one internal and the other external, it will be necessary to have a distinct idea of each to enable pastors to explain the nature of the priesthood now under discussion. Regarding the internal priesthood, all the faithful are said to be priests once they have been washed in the saving waters of baptism. Especially is this name given to the just who have the spirit of God, and who, by the help of divine grace, have been made living members of the great High Priest, Jesus Christ; for, enlightened by faith which is inflamed by charity, they offer up spiritual sacrifices to God on the altar of their hearts. Among such sacrifices must be reckoned every good and virtuous action done for the glory of God”. This passage is followed by the supporting Scriptural texts: Apoc. 1:5, 6; I Pet. 2:5; Rom, 12:1; Ps. I:19.

- Romano Amerio, Iota Unum: A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Twentieth Century, Angelus Press, 1996, p. 187.

Posted April 7, 2021

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |