Consequences of Vatican II

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sisters in Crisis - II

Change of Vocation for the

Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia

Yesterday, I happened across a commentary on the "vision statement" of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Philadelphia. In it they affirm that “challenged by our broken world, we claim our prophetic voice as women, to stand with marginalized persons, and to treasure and care for Earth.”

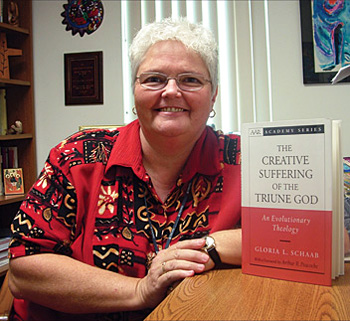

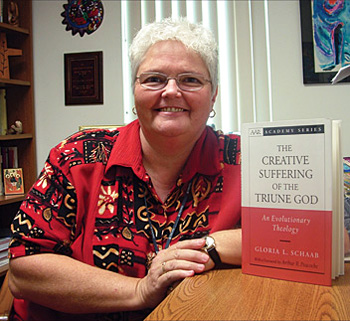

The statement was written in 1994, but Sister Gloria L. Schaab, who by the way rarely uses the title Sister, assures us the words are “as relevant today as it was then.” In my opinion, this Sister of St. Joseph of Philadelphia embodies the progressivist spirit that has hijacked this religious institution.

Following the general trend of post-Vatican II sisters, Gloria Schaab has an advanced degree, teaches at a University (she is associate professor of Systematic Theology and graduate program director in Theology and Ministry at Barry University in Miami Shores, Fl), and is an author and speaker on evolutionary and feminist theology.

Following the general trend of post-Vatican II sisters, Gloria Schaab has an advanced degree, teaches at a University (she is associate professor of Systematic Theology and graduate program director in Theology and Ministry at Barry University in Miami Shores, Fl), and is an author and speaker on evolutionary and feminist theology.

As you can see from the picture where she poses with one of her latest books, titled The Creative Suffering of the Triune God, An Evolutionary Theology, she is a stereotype progressivist sister: The crisp short white hair, the short sleeved noisy shirt, the assertive expression, and the perpetual tolerant smile for everything in the modern world. A smile, however, that is unable to conceal a deep-seated revolt against anything that hints of the “hierarchical or patriarchal image of God.”

In short, there is nothing in her of the old Sister of St. Joseph of the past, and everything of the Vatican II progressivist, semi-masculine, feminist sister of the present.

The 'prophetic voice' of the new woman religious

What does Gloria Schaab tell us about the "prophetic voice" of the women religious on whose behalf she speaks? The clarion call is to address injustice in the world, fighting xenophobia, poverty, and every kind of “discrimination”.

But, she takes the “vision” further to embrace an eco-justice, asserting this as the most fundamental challenge for our times: “To affirm the essential interrelatedness of all creation and creatures in the ongoing evolution of life.”

She summarizes her vision of the new SSJ mission: “I propose three types of prophetic witness that a relational and evolving universe demands: non-hierarchical relationships of inclusivity; transformation of ethical and political systems; and diversity of images for the Divine.”

She summarizes her vision of the new SSJ mission: “I propose three types of prophetic witness that a relational and evolving universe demands: non-hierarchical relationships of inclusivity; transformation of ethical and political systems; and diversity of images for the Divine.”

So, here we have depicted the modern sister of St. Joseph: First, she calls for the destruction of every hierarchical relationship – “forms that oppress” – in the Church and society.

Second, she goes a step further and extends this equality to the “cosmos” – that is, to include the natural world.

Third, she interprets living prophetically in a “relational universe” as transforming ethical and political systems. So, the voice of the modern sister follows Francis’ lead as it helps him do away with “structures of sin,” i.e., Capitalism, and to promote Communism.

Fourth, we are told that living prophetically in a relational universe means “embracing a diversity of metaphors and symbols for the Divine – male and female, human and non-human, individual and communal, ancient and new.”

Sisters like Gloria Schaab will struggle to make us accept God as he/she “reveals Godself” in every religion and era.

In short, our representative post-Vatican II Sister of St. Joseph defends a vision of God and the Church diametrically opposed to Catholic teaching.

The original Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia

The Religious Congregation of Sisters of St. Joseph, originally founded in 1650 in Le Puy, France, was one of the early religious institutions for women outside cloister. Under the patronage of St. Joseph, they dedicated themselves to “the practice of all the spiritual and corporal works of mercy of which woman is capable and which will most benefit the dear neighbor.”

They were disbanded during the French Revolution. Some sisters were imprisoned; five were guillotined. In 1808, they were reorganized by Mother Saint John Fontbonne, who had narrowly escaped execution. In 1836, she sent six sisters headed by Mother Saint John Fournier to St. Louis, Missouri, and the first Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph were officially established in the United States to teach in the mission Church.

In 1847, Mother Saint John Fournier left St. Louis for Philadelphia along with three other sisters to provide care at St. John’s Orphanage for boys. Shortly afterwards, under the advice of Bishop John Neumann, they were given charge of several parochial schools and thus entered on what was to be their chief work in the coming years, the instruction of youth from preschools to colleges.

Their work would expand to include managing hospitals, teaching the deaf, running orphanages and even nursing soldiers on both sides of the fight during the Civil War. But, foremost they were teachers.

In 1884, the Bishops of Baltimore ordered the building of a parochial school near each church where one did not exist. Further, all Catholic parents were instructed to send their children to these schools. This order had a profound impact on teaching institutions like that of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

Because they earned a very small salary, bishops and priests could rely on the teaching services of the sisters without worrying about the costs of paying regular teachers and personnel. The small salaries provided the sisters were returned immediately to support their institution. As the schools multiplied, so also did the call for laborers in the field – teaching sisters.

Let us look at one of these Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia who played a key role in consolidating Catholic education in the burgeoning parochial school system. Because she knew her own vocation had been nurtured by the sisters who taught her, Sister Assisium McEvoy (1843-1939) understood that the teaching sisters served as models for young women considering religious life.

Let us look at one of these Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia who played a key role in consolidating Catholic education in the burgeoning parochial school system. Because she knew her own vocation had been nurtured by the sisters who taught her, Sister Assisium McEvoy (1843-1939) understood that the teaching sisters served as models for young women considering religious life.

“Remember that in the classroom the children are watching you, and you may repel or you may attract,” she reminded the sisters she trained. But, she would also insist: “The numbers means nothing without the spirit.” (1) The spirit was one of fidelity to prayer and the teachings of the Church, as well as the practice of humility and self-abnegation in offering oneself to the service of others.

It is this spirit that is reflected in one of the few pictures that exist of Sister McEvoy, which you can see at right. Her shrewd gaze reveals a person who does not have illusions about persons.

She is a woman who clearly knows people with all kinds of defects, but shows them all a helpful attitude – the wrinkles on her cheeks translate this benevolence. Her lips express that she is used to bearing bitter situations. But, the disciplined and calm position of her body, seated on the bench, shows that she surmounts these problems through a confidence born from frequent recourse to Divine Providence.

The efforts to attract new vocations were certainly successful. In Philadelphia the Sisters of St. Joseph doubled in size between 1903 and 1925, when professed members numbered more than one thousand and the novice houses were filled. By the mid-1960s, vocations were still flourishing and the Congregation numbered close to 2,500 professed sisters in the U.S. And always, the need was greater than the supply to fill the teaching positions in the growing Catholic school system.

The efforts to attract new vocations were certainly successful. In Philadelphia the Sisters of St. Joseph doubled in size between 1903 and 1925, when professed members numbered more than one thousand and the novice houses were filled. By the mid-1960s, vocations were still flourishing and the Congregation numbered close to 2,500 professed sisters in the U.S. And always, the need was greater than the supply to fill the teaching positions in the growing Catholic school system.

Each woman who entered the Institution – most of them young, between the ages of 18 and 25 – became part of the family of the Sisters of St. Joseph, receiving a new name to symbolize her abandonment of the world and her entrance into a new life: A life whose purpose was her personal sanctification as well as the service of neighbor, a life that had remained virtually unchanged for several hundred years.

The life of a sister was a silent example of following the Way of the Cross. The very figure of the Sisters of St. Joseph, with their white circular cuimpe and linen cornette, a large Crucifix around the neck and a Rosary at the side, was permanently etched in the minds of students as a living symbol of self-sacrifice and authentic Catholic charity.

Then, came Vatican II

The Vatican II decree Apostolicam actuositatem on renewal of religious life called on sisters to adapt their religious life to the 20th century as a “sign of the times.” It was not long before new commands were coming from the Superiors who were gathering to study how to apply to their convents the resolutions of the Council.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia took a bit longer than most Religious Congregations to abandon their habit. The trademark cornette was present until 1974, when it became a modified habit and veil. But, by the 1980s the habit was completely gone, along with any trace of the old formation and customs.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia took a bit longer than most Religious Congregations to abandon their habit. The trademark cornette was present until 1974, when it became a modified habit and veil. But, by the 1980s the habit was completely gone, along with any trace of the old formation and customs.

Gone also were the rules separating the religious women from their worldly friends and family. Likewise abolished were the censorship of mail, restrictions on traveling, and living in traditional convents. The sisters who remained were encouraged to get masters and doctorates and pursue careers as salaried professionals.

The result was a drastic drop in religious vocations. The Sisters of St. Joseph lost half their number by 2008. Today’s remaining 1,000 sisters are mostly aging women, with a median age of 70. Last year there were only five Sisters of St. Joseph who made their final vows, and those were late vocations who have embraced the “prophetic mission” outlined above by Gloria Schaab.

Yes, there are Offices of Mission Integration and sophisticated orientation programs to educate the public about the vision and history of their Congregation to keep the legacy alive, but they do not bring in new sisters.

Where are the droves of young idealistic girls who were eager applicants for the novitiate as late as the 1960s? They are gone, along with the discipline, the recitation of the Prime and Compline and other community prayers and devotions, the habit with its Rosary at the side, and the spirit of the Institution.

They were replaced by the ideals of the Revolution: To attack inequality and the Western political-economic system, and to promote Socialism and Ecology.

Posted July 9, 2014

The statement was written in 1994, but Sister Gloria L. Schaab, who by the way rarely uses the title Sister, assures us the words are “as relevant today as it was then.” In my opinion, this Sister of St. Joseph of Philadelphia embodies the progressivist spirit that has hijacked this religious institution.

Dr. Gloria Schaab, the new face of the Sisters of St. Joseph

As you can see from the picture where she poses with one of her latest books, titled The Creative Suffering of the Triune God, An Evolutionary Theology, she is a stereotype progressivist sister: The crisp short white hair, the short sleeved noisy shirt, the assertive expression, and the perpetual tolerant smile for everything in the modern world. A smile, however, that is unable to conceal a deep-seated revolt against anything that hints of the “hierarchical or patriarchal image of God.”

In short, there is nothing in her of the old Sister of St. Joseph of the past, and everything of the Vatican II progressivist, semi-masculine, feminist sister of the present.

The 'prophetic voice' of the new woman religious

What does Gloria Schaab tell us about the "prophetic voice" of the women religious on whose behalf she speaks? The clarion call is to address injustice in the world, fighting xenophobia, poverty, and every kind of “discrimination”.

But, she takes the “vision” further to embrace an eco-justice, asserting this as the most fundamental challenge for our times: “To affirm the essential interrelatedness of all creation and creatures in the ongoing evolution of life.”

Sisters of St. Joseph marching for the rights of immigrants

So, here we have depicted the modern sister of St. Joseph: First, she calls for the destruction of every hierarchical relationship – “forms that oppress” – in the Church and society.

Second, she goes a step further and extends this equality to the “cosmos” – that is, to include the natural world.

Third, she interprets living prophetically in a “relational universe” as transforming ethical and political systems. So, the voice of the modern sister follows Francis’ lead as it helps him do away with “structures of sin,” i.e., Capitalism, and to promote Communism.

Fourth, we are told that living prophetically in a relational universe means “embracing a diversity of metaphors and symbols for the Divine – male and female, human and non-human, individual and communal, ancient and new.”

Sisters like Gloria Schaab will struggle to make us accept God as he/she “reveals Godself” in every religion and era.

In short, our representative post-Vatican II Sister of St. Joseph defends a vision of God and the Church diametrically opposed to Catholic teaching.

The original Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia

The Religious Congregation of Sisters of St. Joseph, originally founded in 1650 in Le Puy, France, was one of the early religious institutions for women outside cloister. Under the patronage of St. Joseph, they dedicated themselves to “the practice of all the spiritual and corporal works of mercy of which woman is capable and which will most benefit the dear neighbor.”

They were disbanded during the French Revolution. Some sisters were imprisoned; five were guillotined. In 1808, they were reorganized by Mother Saint John Fontbonne, who had narrowly escaped execution. In 1836, she sent six sisters headed by Mother Saint John Fournier to St. Louis, Missouri, and the first Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph were officially established in the United States to teach in the mission Church.

In 1847, Mother Saint John Fournier left St. Louis for Philadelphia along with three other sisters to provide care at St. John’s Orphanage for boys. Shortly afterwards, under the advice of Bishop John Neumann, they were given charge of several parochial schools and thus entered on what was to be their chief work in the coming years, the instruction of youth from preschools to colleges.

Their work would expand to include managing hospitals, teaching the deaf, running orphanages and even nursing soldiers on both sides of the fight during the Civil War. But, foremost they were teachers.

In 1884, the Bishops of Baltimore ordered the building of a parochial school near each church where one did not exist. Further, all Catholic parents were instructed to send their children to these schools. This order had a profound impact on teaching institutions like that of the Sisters of St. Joseph.

Because they earned a very small salary, bishops and priests could rely on the teaching services of the sisters without worrying about the costs of paying regular teachers and personnel. The small salaries provided the sisters were returned immediately to support their institution. As the schools multiplied, so also did the call for laborers in the field – teaching sisters.

Sister Assisium McEnvoy educated many young women and inspired them to take the habit

“Remember that in the classroom the children are watching you, and you may repel or you may attract,” she reminded the sisters she trained. But, she would also insist: “The numbers means nothing without the spirit.” (1) The spirit was one of fidelity to prayer and the teachings of the Church, as well as the practice of humility and self-abnegation in offering oneself to the service of others.

It is this spirit that is reflected in one of the few pictures that exist of Sister McEvoy, which you can see at right. Her shrewd gaze reveals a person who does not have illusions about persons.

She is a woman who clearly knows people with all kinds of defects, but shows them all a helpful attitude – the wrinkles on her cheeks translate this benevolence. Her lips express that she is used to bearing bitter situations. But, the disciplined and calm position of her body, seated on the bench, shows that she surmounts these problems through a confidence born from frequent recourse to Divine Providence.

The first mission the Sisters undertook in Philadelphia was an orgphanage for boys

Each woman who entered the Institution – most of them young, between the ages of 18 and 25 – became part of the family of the Sisters of St. Joseph, receiving a new name to symbolize her abandonment of the world and her entrance into a new life: A life whose purpose was her personal sanctification as well as the service of neighbor, a life that had remained virtually unchanged for several hundred years.

The life of a sister was a silent example of following the Way of the Cross. The very figure of the Sisters of St. Joseph, with their white circular cuimpe and linen cornette, a large Crucifix around the neck and a Rosary at the side, was permanently etched in the minds of students as a living symbol of self-sacrifice and authentic Catholic charity.

Then, came Vatican II

The Vatican II decree Apostolicam actuositatem on renewal of religious life called on sisters to adapt their religious life to the 20th century as a “sign of the times.” It was not long before new commands were coming from the Superiors who were gathering to study how to apply to their convents the resolutions of the Council.

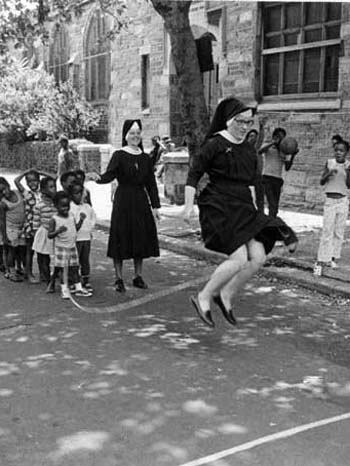

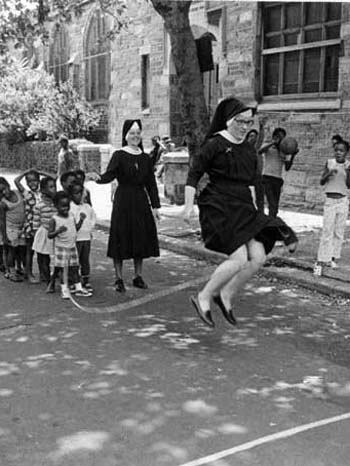

The modified habit entered,

along with a new spirit of relaxation and 'fun'

Gone also were the rules separating the religious women from their worldly friends and family. Likewise abolished were the censorship of mail, restrictions on traveling, and living in traditional convents. The sisters who remained were encouraged to get masters and doctorates and pursue careers as salaried professionals.

The result was a drastic drop in religious vocations. The Sisters of St. Joseph lost half their number by 2008. Today’s remaining 1,000 sisters are mostly aging women, with a median age of 70. Last year there were only five Sisters of St. Joseph who made their final vows, and those were late vocations who have embraced the “prophetic mission” outlined above by Gloria Schaab.

Yes, there are Offices of Mission Integration and sophisticated orientation programs to educate the public about the vision and history of their Congregation to keep the legacy alive, but they do not bring in new sisters.

Where are the droves of young idealistic girls who were eager applicants for the novitiate as late as the 1960s? They are gone, along with the discipline, the recitation of the Prime and Compline and other community prayers and devotions, the habit with its Rosary at the side, and the spirit of the Institution.

They were replaced by the ideals of the Revolution: To attack inequality and the Western political-economic system, and to promote Socialism and Ecology.

Before Vatican II, above, a constant influx into religion of youthful idealistic women;

today, almost all are aging seniors who look like everyone in the modern world, below

Posted July 9, 2014

______________________

______________________