|

Women and Men in Society

Hepburn and Mephistopheles

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

The recent death of actress Katharine Hepburn at age 96 has engendered any number of eulogies of this media favorite whose career ran six decades. She is being praised both as a strong moral person and as a vibrant indomitable rebel who was an eminent role model for women. To set the record straight for the unknowing or the naive, let me say that both of these renderings are completely false.

What kind of morality is this?

It is bad enough to see the secular media depicting Hepburn as a high-principled woman of morals, an honest, frank soul always living by her convictions. But it is absolutely shocking to see a diocesan newspaper, even of the notoriously liberal Los Angeles Diocese, print an article describing Katharine Hepburn as having “Old World values,” and romanticizing her illicit love-affair with Spencer Tracy, a married Catholic man.

“She did not smash, but lived by a set of values so traditional that they would shock all those who are making her a mother goddess of breaking rules and improvising one’s way through life,” the article by Eugene Cullen Kennedy read (“Spencer called her Kath,” The Tidings, July 11, 2002). Sifting through her biographical data, I could not find this “set of traditional values” she supposedly lived by.

Eight-year-old Katharine (left) poses with her mother |

What I found was that she was raised from childhood in a notoriously liberal environment. Long before it became “fashionable,” her mother was a feminist and an advocate of abortion-rights. In fact, Hepburn’s influential mother was co-founder with Margaret Sanger of Planned Parenthood. It was these “values” she instilled in Katharine, who supported women’s rights all her life, became a board member of Planned Parenthood, and asked that donations made after her death should be directed to that organization.

During her college years at Bryn Mawr, Hepburn lived a wild party life. Her penchant to break conventions was already apparent in her unorthodox dress: baggy men’s trousers, oversized sweaters and men’s shirts, shocking even for the extravagant tastes of the “roaring ‘20s.”

When she finally decided to marry, she insisted not only that her wealthy fiancé change his name from Ludlow Ogden Smith to Ogden Smith Ludlow so she would not have the plain name of Kate Smith, but also that she would continue her stage career. After several years, she went to Mexico for a divorce. “I don’t believe in marriage,” she later stated. “It’s bloody impractical to love, honor, and obey.” These are not exactly traditional values.

And so she began the string of illicit and open love-affairs with powerful men such as Hollywood agent Leland Howard and eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes. And there were others. In her autobiography egotistically titled “Me,” a lot of ink is spent reminiscing about her immoral relationships with the “men in my life.” Children? Of course not. “I would have been a terrible mother. I’m basically too selfish,” Hepburn laughs, and this is what the fawning media presents as an admirable example of her frank and honest spirit.

The grand enigma is the general public sympathy Hepburn elicited – even among Catholics – for her scandalous 25-year up-and-down relationship with Spencer Tracy. Hepburn always said she respected Mrs. Tracy, and so she and Spencer did not appear in public, although the whole world knew about her affair. It was a strange kind of respect. Ironically, she called herself and Tracy the “perfect American couple."

Nor was Hepburn traditional in her views and affiliations. “I’m an atheist and that’s it. I believe there’s nothing we can know except that we should be kind to each other and do what we can for other people.” Based on her utilitarian vision of the world, she supported euthanasia. “If I got sick and was no longer of any use to myself or anyone else, I would find a way of ending it, “ she once said.

In a 1990 Associated Press interview, she offhandedly summarized her thinking on the afterlife: “I’m what is known as gradually disintegrating. I don’t fear the next world, or anything. I don’t fear hell, and I don’t look forward to heaven.” It is an eerie echo of Faust’s bold words in his study: “I fear neither the devil nor hell.”

A new model for women: the maker of her own fate

Since we have wandered into Goethe’s celebrated poem, permit me to sketch an imaginary, but perhaps not so improbable Faustian scene. It is the 1930s, and the wily Mephistopheles is chuckling over his new tool to ensnare women from moral and upright lives: Hollywood. Yes, the devil was doing quite well finding new romantic models for young women to move them away from family life and responsibilities. He had now, for example, the smoldering, languid and aloof “grande dame” style of a Gloria Swanson, to buttress the soft, fragile, and helpless Victorian heroine.

“All well and good, so far as it goes,” he gloated. But something was missing. He needed a film star willing to break the very conventions of femininity – a tough, rough-talking, bold and masculine kind of woman who would dress and talk like a man, a free and independent spirit to be a role model for new kind of “emancipated woman” of the world he had in mind for the future.

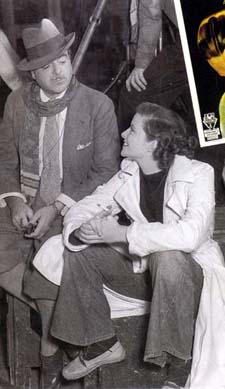

Above, with director Lowell Sherman |

He’d had his eye on Katharine Hepburn for quite some time. Her background was good, her penchant for masculine dress already established, her free-spirited and revolutionary views on marriage and sexual conventions ideal. Although she had landed some good roles in the ‘30s, she was still not popular. Her critics dismissed her acting as shallow, her voice as harsh, her features too horsy. Because of her difficult temperament and uneven performances, she had been labeled as box office poison.

The time was right to strike a deal with this strong-minded woman hell-bent on becoming a great star and writing her own ticket. You can have it all, perhaps he whispered in her ear about this time. All the awards and honors you can imagine, all the romances you want, all the fame possible in this life. I’ll give you 100 years – give or take a few years.

A pact like this is perfectly plausible, and it would explain many things.

Whether a deal with the devil was made or not, something changed about this time. After the stunning and unexpected theater success with The Philadelphia Story, for which she bought the film rights, she returned to Hollywood on her own terms in 1939, a virtual unknown who held a contract for a role in A Bill of Divorcement at the almost unheard-of fee of $1500 a week.

One triumph followed another from there. By the end of her six-decade career, she had made some 50 films and television movies, received a record 12 Academy Award nominations, and won an unprecedented four Oscars for Best Actress – three of them awarded after her 60th birthday. A Katharine Hepburn Garden in the United Nations Dag Hammarskjold Plaza was even dedicated to her on her 90th birthday.

Hepburn: a forerunner of the modern feminist woman |

She certainly would have kept her part of the bargain, if the hypothetical bargain existed. She lived, as she often asserted “like a man,” by herself, paying her own bills, and ultimately answering to nobody. She “chose” not to marry, not to have children, always, as she was fond of saying, “paddling the g—d— boat by myself.” This expletive was familiar on her tongue - she helped initiate the easy familiarity the modern woman shows with vulgar language.

“With stout resolve,” reports a fashion book, “she almost single-handedly broke down the dress code for women” by insisting on wearing men’s trousers on set and off, everywhere and all the time. Her style was so informal and untraditional that she never, even after becoming a star, owned a dress or skirt of her own. One of her many awards came from the Council of Fashion Designers of America in 1986 – in recognition of her role as non-conformist in modern fashion.

In fact, the “famous yet enigmatic Ms. Hepburn” is hailed and remembered today as a prototype of today’s modern woman – independent, free in her moral behavior, unencumbered by religion, traditional values or conventions of the past.

I don’t know if the ending of Hepburn’s story followed Goethe’s happy ending with the salvation of Faust’s soul, or Marlowe’s more grim and realistic finale. One thing is for certain, it didn’t follow a Hollywood script. It was a private and final account rendered by the revolutionary woman to the God she didn’t believe in.

Posted July 16, 2009

|

Related Works of Interest

|

Women and Men | Cultural | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|